Writing Bantling: family history and fictional narrative

Most children unquestioningly accept their parents as such, and don’t have much of curiosity about their lives pre-parenthood.

This was certainly true of me, I think. In spite of being aware that most children also had two sets of grandparents, I can’t remember wondering why we only had one set, on my mother’s side.

I do remember knowing about the moon-shaped scar under father’s bottom lip, a consequence of a childhood accident when a bed-bouncing session caused the bed and ceiling to collapse. I had the impression from this story that my father, Ron, grew up with siblings.

Roofers that I randomly employed when I moved to south London had the name of the family he grew up in, my father let slip. They displayed no interest in finding a family connection with me and I didn’t press it. Years later, after I’d belatedly recognised the possible significance for my father, I realised their surname was an unusual one. People who shared it lived in a small area of south-east London, at least in the early twentieth century.

From the few other nostalgic snippets Ron shared when I moved to south London in the early 1980s, and from his birth certificate, found after his death in 1996, along with the birth certificate of Mabel Georgina Orienta Russell, I started trying to find out more.

His birth certificate – mother shown as Mabel Russell, father unknown – showed that he was born in Clapham Maternity Hospital (later Stockwell Studios for artists, now flash housing), to an unmarried woman who was a grocer’s book-keeper from the Isle of Wight.

The history of the hospital was completely unknown to me – and fascinating. It was founded in 1889, by Dr Annie McCall, with the dual purposes of enabling women to treated ‘by their own sex’, and of giving women doctors a place to train. (McCall herself had to train overseas – women being specifically disbarred from receiving training in Britain at the time).

It was, I think, the first hospital in the country where women were treated only by women. They offered services to the many impoverished women in the Clapham and Battersea area, and also to a select group of ‘otherwise respectable’ unmarried women expecting their first child.

How, I wondered, did a young woman from the Isle of Wight manage to find out about, get to, this hospital? What happened to the children born here?

Years after the roofing job, I tracked the roofers’ antecedents across Kennington and Clapham and Peckham, in the census, electoral rolls and various other records and directories.

Some parts of the family had businesses and settled addresses, but it became clear the family unit that Ron ended up living with was very poor, almost itinerant before they settled one street away (long redeveloped) from the Peckham extension to the Surrey Canal (largely now covered by Burgess Park and the Surrey Canal Walk).

How, I wondered now, had the life of the young woman at the hospital intersected with an impoverished family in such a way that her child ended up with them, taking their name and with no apparent further contact?

All this happened three years before adoption in 1926 took the legal form it has now, so I found no records, official or otherwise.

I knew from my father that although he was close to the woman who brought him up – his mother to all intents and purposes – his relationship with his ‘father’ had broken down in the 1940s. As I later found out, this man was still alive when our family arrived from Australia in 1959, but as far as I know Ron did not try to make contact with him.

Mabel Georgina Orienta died in infancy, I discovered. I don’t know if Ron tried to find her or not – but he would not have succeeded if he had. He’d got hold of the certificate in the early 1960s. Only manual records were available at the time from searches at Somerset House.

I was luckier in a way, with access to the internet – I found her death certificate and then, preceding her birth by a few years, another Mabel Russell. This Mabel seemed to have lived most of her life on the Isle of Wight, marrying and having several children. It’s more likely this is the Mabel who was my father’s birth mother. The pre-war family facts petered out, though I had luck with the war time history.

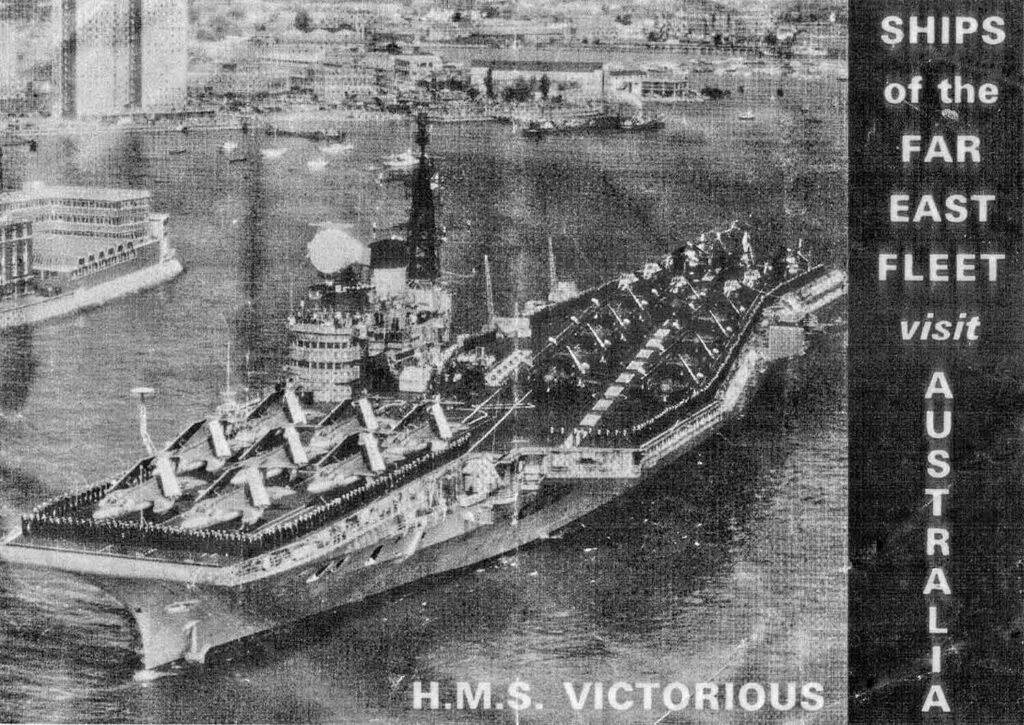

Like Sam, Ron served in the Fleet Air Arm on HMAC Victorious and emigrated to Australia post-war, where he met my mother, the daughter of Russian refugees. Shortly before they were married, Ron ran into someone who had also served on the Victorious as a mechanic, though in the Air Force.

Andrew Hyde, and his young wife, Mary, became life-long friends. When he learned I was writing this book, Andrew gave me a copy of the diary he kept for some years during the war, and I’ve drawn heavily on that, though also edited and adapted it to serve the fictional narrative.

The gaps in my knowledge became more defined, more beguiling and more insistent as the social and historical material firmed up. Nature abhors a vacuum. Imagination moved into those spaces, linking them up, making pathways and connections between the possibilities offered by the research material.

Initially using the given names of the individuals, as far as I could locate them, the fictional characters only took on their own identities when I gave them new names. Whether from a misplaced sense of ‘respect’ or constraint around what is or is not appropriate to think or write about a parent or their parent, using Ron and Mabel’s birth names proved limiting, even though I was making up their stories.

It was only once they had names unrelated to history that the characters took on lives and stories of their own. This was both startling and liberating. So, I found myself constructing a story about an unmarried mother, Violet, a child, Sam, and the people around them – Ellen, Harry, Alice and others.

Writing an invented narrative for fictional characters, finding some sort of imaginary resolution to situations that never existed satisfied some itch in me about how little I actually knew about my father’s early life. My father never met his birth mother. I don’t know how he felt about this, other than the hint provided by Mabel Orienta’s birth certificate, counterpoised by my mother’s assertion, after Ron died, that she’d persuaded him, years before, that ‘if he wasn’t good enough for them then, then they weren’t good enough for him now’.

I’m not convinced that my father was ever persuaded not do something he wanted to or felt he should. Equally, I can’t imagine it was a straightforward decision in any respect. I like to imagine that Ron had a pretty nuanced position: that the best form of retort (if not revenge) is to live well – which he did – but also to allow that some questions never quite went away. And he might have wondered if Mabel Russell would or wouldn’t have wanted to answer them, or been able to, even if he’d been able to ask her. Never complain, never explain, never apologise, he reiterated from time to time, along the advice that it is better to have memories than regrets.

Sometimes, I think, part (but only part) of the trick of living well, or well enough, is to learn to live with unknowing and uncertainty, to tolerate ambivalence, to welcome difference, to know that there is never a single, uncompromised way to understand either ourselves or what happens in the world we move within.